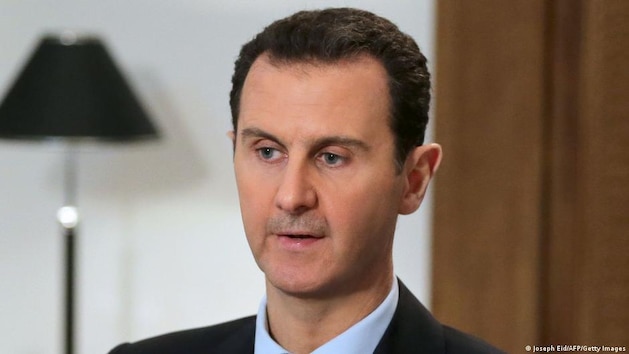

They have been irreconcilable for years, and now Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his Syrian counterpart Bashar al-Assad could get closer to each other again. This is what Erdogan indicated at the end of last week. He no longer ruled out a meeting with Assad, he said. With regard to Syria, he spoke of a new peace process in which Russia was also involved alongside Turkey and Syria.

First there was a meeting of the intelligence chiefs and defense ministers in Moscow. According to Erdogan, the foreign ministers of the three countries should now meet – according to some media reports, this could happen as early as Wednesday (11 January).

The political overtures of his longtime rival Erdogan should come in handy for Assad, believes Bente Scheller, head of department and Middle East expert at the Heinrich Böll Foundation. “Of course, he hopes that this will give him a diplomatic boost.” Critics already see the danger of Assad’s gradual return to the international stage, while opponents of the Syrian government feel betrayed by Erdogan and have been protesting the planned rapprochement for days.

But how far would this go? In any case, Assad’s second hope is not likely to be fulfilled any time soon, namely that of material donations, on which the completely destroyed country is absolutely dependent. According to Scheller, there is hardly a country that is currently willing to invest in Syria.

It seems clear that the realities in the country also set limits to any political appreciation. Nevertheless, Assad is now in a comparatively strong position, says political scientist Christopher Phillips from Queen Mary University in London. “He won the war in that he controls most of the country, although by no means all of it.” It was a Pyrrhic victory, as the country was destroyed. “But in military terms, the opposition no longer represents a serious alternative to Assad.”

This is another reason why Erdogan seems interested in reorganizing his relationship with Assad. For a long time, Turkey was one of the most important supporters of the armed Syrian opposition and has maintained to this day that it does not want to let Assad’s political opponents fall. After the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Erdogan had for a long time been counting on the future of the neighboring country without Assad as president and ruled out any contact with him. He has now deviated significantly from this course.

Because now Erdogan obviously sees Assad as a partner with whom some of his own political goals can be better achieved. For years he has been trying to push back the Syrian-Kurdish PYD party and its “People’s Defense Units” (YPG) from the Syrian-Turkish border area. Both are closely associated with the Kurdish Workers’ Party PKK, which considers Ankara public enemy number one. In order to expel forces close to the PKK from the border region, he had parts of north-eastern Syria attacked by the military last year, and there is still a threat of invasion. Erdogan apparently hopes that the expulsion of Kurdish militias will be easier to achieve if Assad is on board.

But it is unclear whether this calculation will work out, says Bente Scheller. It is true that Assad has no particular sympathy for Kurdish attempts at autonomy. However, for him, their representatives are the most important contact partners in the north-east of the country. “That’s why I’m not sure that Assad and Erdogan can agree on a common course regarding the Kurds.”

In addition, Erdogan is looking for a solution for the approximately four million Syrian refugees who Turkey is currently hosting. In view of the galloping inflation – in October it was over 85 percent compared to the previous year – the people in need of protection are becoming an ever greater burden for the state, apparently also from the point of view of many Turkish citizens. This could affect Turkey’s presidential elections in June. Erdogan has an interest in the refugees returning to Syria as quickly as possible.

However, the Assad regime has no interest in a comprehensive return of the refugees, says Bente Scheller. “That’s why there shouldn’t be any real agreement between Erdogan and Assad on this point either.”

In addition to Turkey, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) also clearly see reason to seek contact with the long-isolated Syrian government. In the middle of last week, the UAE’s Foreign Minister, Abdullah bin Zayed Al-Nahyan, traveled to Damascus, where he also met Assad. The UAE, along with Saudi Arabia, is Iran’s major competitor in the region. In addition to realpolitik realization that for the time being there is hardly any way around Assad in Syria, their aim should not least be to limit Iran’s influence in Syria as much as possible. However, it seems questionable whether the UAE could manage to limit the presence of the Lebanese Hezbollah militia and other Iranian-backed forces and militias. Because they support the Assad regime to a degree that the UAE could not afford, even if they wanted to. Assad depends on them. By harboring Hezbollah in Syria, Assad is of course strengthening its clout – against Israel, for example – and thus also Iran’s. In this respect, the diplomatic representatives of the UAE must be prepared for further difficult talks.

It will be interesting to see how Russian influence in Syria develops. It is true that Russia’s military engagement alongside Assad undisputedly saved him from military defeat at the time. In the meantime, however, Russia’s forces seem to have been weakened by its war of aggression in Ukraine, which went differently than planned. And diplomatically, Russia has been largely isolated ever since. In this situation, Moscow should find it more difficult than before to keep its influence in Syria constant and not increasingly lose to its political partner, but also to its competitor Iran.

At the same time, however, Assad still has to reorganize and secure his own hold on power in Syria – and for that he needs Russia and Iran. Syria expert Bente Scheller explains that it is not at all easy for Assad to secure his own power, referring to fighting between regime forces and the opposition that has flared up again and again, as well as between various regime militias in southern Syria. There are also increasing public demonstrations against Assad there, which could well lead to acts of violence. “At first glance, Assad’s power appears to be solid. In fact, the country he officially governs is controlled in many places by individual mafia-like militias. And of course they have a freer hand if Iran and Russia don’t intervene to regulate it.”

And the western states? They currently have sanctions on Syria. Christopher Phillips from Queen Mary University in London says they find it extremely difficult to imagine talks with Assad. Most western countries still see Assad as a war criminal. It is true that for them, too, many problems can hardly be solved without an official contact person in Syria, above all the refugee issue and generally stopping death and violence. Nevertheless, direct talks by Western politicians with Assad do not seem conceivable for the time being, except perhaps if he were to make previously unimaginable concessions. However, what these could look like is currently completely unclear, says Christopher Phillips. But in terms of realpolitik, it cannot be ruled out that the West might need Assad again at some point. Assad is also aware of this.

Bente Scheller has a clear opinion on this: A creeping political rehabilitation and thus a permanent retention of Assad in power would be a catastrophe for the political culture inside and outside the region, she says. “Because much of what Assad achieved was only possible through a massive breach of international norms. Because it is of course a dangerous precursor for all other conflicts when the stronger or the supposedly stronger prevails here in violation of the current and applicable law.”

The situation for many Syrian refugees therefore continues to look bleak. Many of them would not be able to return to a Syria ruled by Assad because they are threatened with political persecution there and with it danger to life and limb. In many cases – not least in Turkey – they hardly feel welcome in the countries to which they have fled. If Assad stays in power, many of them will have no prospects for the future.

Collaboration: Catherine Schaer

Author: Kersten Knipp

As the American “Vogue” reports, the supermodel Tatjana Patitz died. She was 56 years old.

When I read the police report today, I was honestly shocked: It said there were families with small children among the occupiers of the lignite town of Lützerath. Small children? In the battle zone against global warming! Are you crazy?

The original of this post “Syria’s Ruler Assad: Gradual Return to the International Stage?” comes from Deutsche Welle.