In view of China’s decades-long one-child policy, the population of the People’s Republic is getting smaller and smaller. The Chinese population development could thus destroy Xi Jinping’s plan for a modern industrial state.

Now it’s official: China’s population is shrinking. This development was expected given a one-child policy that had lasted for three decades. The population of the People’s Republic of 1.4 billion people is said to have shrunk by around one million people for the first time last year. This number may not sound huge given the total number of residents.

However, this number will now increase every year and will have increased to a total of 110 million people by 2050. Depending on the birth rate used to project the population of China in future years, the population could even drop to 488 million people by the year 2100. A slightly better scenario assumes 767 million people.

While not enough children are being born, the population of the People’s Republic is also aging: between five and ten million people are now retiring from working life every year. In 2035, 30 percent of the population, that is around 400 million people, will be 60 years and older.

This could mean the death knell for the development of the People’s Republic into a modern industrial state: China is getting old before it gets rich. Beijing will not be able (and will not) compensate for this development through immigration .

As with many figures reported from the People’s Republic, the accuracy of the information cannot be relied on here either. However, since the provincial governments receive grants from Beijing in relation to the population, there is reason to believe that the population figures reported from the regions are too high and in fact there are already fewer people living in China than the Communist Party claims.

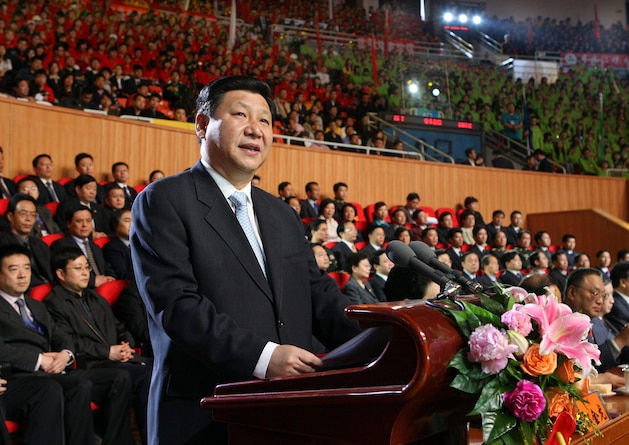

Ruler Xi does not need the news of the population decline: he has set himself the goal of transforming the People’s Republic into a prosperous industrial nation by 2049. He appropriately calls this process the “rejuvenation of the nation”. So far, this process has been more of a regression to the maxist-Leninist doctrine, controlled state capitalism, extreme nationalism and a leader cult strongly reminiscent of fascism. In Xinjiang, Xi has locked up more people in concentration camps than since Hitler’s dictatorship.

Military spending has been rising steadily for years, and the arsenal of nuclear warheads has grown to around 400. Even if Beijing will not officially admit it: Xi needs people to expand the army and to keep the Chinese economy as the largest in the world palatable to the rest of the world. Only if China remains interesting in this way will Beijing have enough potential to blackmail countries that need the Chinese sales market.

Under Xi, the threat of the military has become part of everyday life for many Asian countries. The People’s Republic has border disputes with all its neighbors, above all with India, which will surpass the population of the People’s Republic this year and become the most populous country on earth. With Delhi, the dispute between the two countries has already escalated violently, with dead soldiers on both sides.

Xi is in a hurry to establish facts in the western Pacific: he and his vassal North Korea have signaled aggressiveness towards South Korea and Japan to the east and the Philippines to the south, underscored by missile tests and risky maneuvers. And the island democratic republic of Taiwan is what Xi would like to conquer and violently “reunite” with the mainland.

But sooner or later the leader will run out of manpower: China can neither maintain a war economy nor an army in the long term that could put Xi’s imperial wishes into practice.

Red Alert: How China’s aggressive foreign policy in the Pacific is leading to a global war

The fact that this leads to panic in Beijing has already been shown when Hong Kong’s democracy was leveled. The treaties actually stipulated that Hong Kong could keep its special status (“one country, two systems”) until 2049. There was no obvious reason to strike thirty years earlier. Except when you consider that in 2049 there might not be enough men and women of legal age left to rein in Hong Kong.

Because in addition to the people in the formerly autonomous metropolis, Beijing also oppresses people in Tibet, Inner Mongolia and, as already mentioned, Xinjiang. If they all wanted to free themselves from Beijing’s yoke at once, the army could no longer stop this quest for freedom.

This could also be the reason why Xi has already committed his army to dark times and, at least according to some military experts, prefers to contemplate conquering Taiwan sooner rather than later. It will not only take thousands of soldiers to conquer Taiwan, but at least as many more to occupy the island and hold it as a Chinese conquest.

It also doesn’t look like the people of China, cheered on by Xi’s nationalist slogans, are willing to have more children. The People’s Republic is following the modernization course that Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have also gone through: the cost of living is rising, the need for better educated people is growing. These opt for smaller families.

In addition, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, people in South Korea and Taiwan also decided because of this development that they would rather live in a democracy in the future.

That the same could happen in China is not impossible, and thus Xi Jinping’s nightmare. At the moment, however, this is nothing more than music of the future. It is all the more relevant now to price in the population development in the People’s Republic in scenarios that try to make predictions for what Xi Jinping could plan militarily, be it in relation to Taiwan, be it with regard to other trouble spots, of which the ruler has accumulated numerous.

Alexander Görlach is Honorary Professor of Ethics at Leuphana University in Lüneburg and Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs in New York. After stints in Taiwan and Hong Kong, he has focused on the rise of China and what it means for East Asian democracies in particular. From 2009 to 2015, Alexander Görlach was also the publisher and editor-in-chief of the debate magazine The European, which he founded. Today he is a columnist and author for various media. He lives in New York and Berlin.